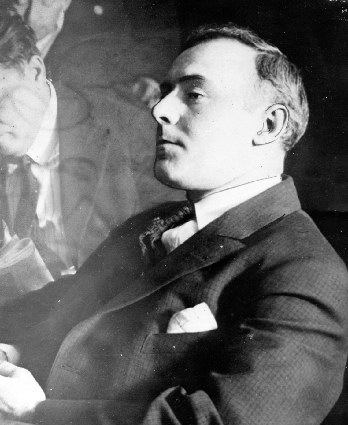

Born to Scots / Irish heritage John Y. McKane was born in County Antrim, Ireland on August 10, 1841, the McKane family moved to Gravesend before he was two years old. In 1864 John McKane was 21-years-old and learning the carpentry trade, by 1866, he had branched off on his own as a carpenter and builder in the Sheepshead Bay area.

In 1868, he got his first taste of public office, as a constable with a one-year term. Diligent and hardworking, McKane continued to operate his construction business on the side. He was the kind of man who dreamed the American dream, who sought to make something of himself. He got married, settled down at Sheepshead Bay and had a family. By all accounts he started off honest enough, he was even superintendent of the Sheepshead Bay Methodist Episcopal Sunday school. But once he got a taste for power everything changed.

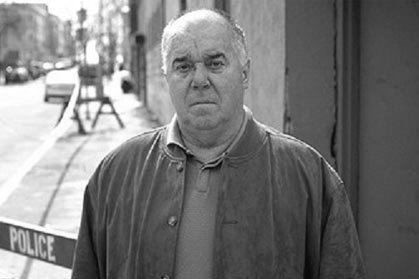

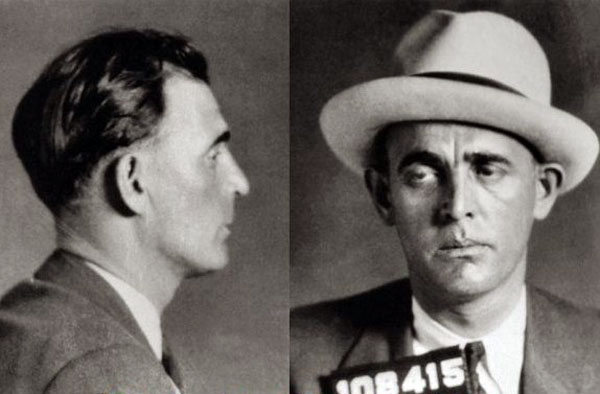

The following year he was elected town commissioner. In 1879 he was town supervisor and eventually became head of the town board of health, the water board and served as the excise commissioner, meaning he was responsible for collecting taxes. But he really consolidated his power when he became the chief of police in 1881. McKane was a large man with a substantial beard and mustache, McKane could sometimes be seen patrolling the beaches in his swim trunks with a club in hand.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle once reported “For ten years prior to his conviction he was in every sense the autocrat of Gravesend” wrote the Eagle. “He was feared and to a certain extent beloved. No ruffian was so hardened as to refuse to obey the command when summoned ‘to see the chief at headquarters.”

He quickly realized that having his position as police chief & political influence would greatly benefit his construction business. It allowed him to acquire permits that other people could not get, rezone land to his benefit, hold up projects with red tape unless they used his company, and be in the decision making of every major construction project around the town.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle reported that “just about every theater, hotel, resort, restaurant, saloon and racetrack that set up shop in Gravesend had to pay McKane for ‘protection’ or ‘favors,’ and he found all sorts of self-aggrandizing reasons to charge ‘fees.’ For example, after he established his own artificial ice plant on Coney Island, he imposed a license fee of $200 on every wagon peddling natural ice, putting them all out of business.”

In 1884, the presidential election was held between Grover Cleveland the Democratic candidate and James G. Blaine the Republican one. In Gravesend, the head of the Democratic Party was John Y. McKane, and the head of the Republican Party was also John Y. McKane. Usually whichever ticket McKane voted for, the whole town usually followed suit.

McKane talked the situation over with his lieutenants, Kenny Sutherland and Dick Newton. After a meeting with the leaders of Tammany Hall, McKane decided to side with them and support Cleveland. Word went out to every hotel, restaurant, bar, parlor and brothel that McKane expected everyone to do their duty and vote a straight Democratic ticket. All of the town’s wards voted in the same building, making it that much easier for voters to be intimidated into voting McKane’s way. Monitors from both parties were assigned to keep an eye out for voting irregularities, or in this case to ensure them.

The election turned out to be very close, with the outcome of the election hanging on New York’s electoral vote. Cleveland and Blaine were running neck and neck in New York State. Just when it appeared that there might be a tie vote in New York State, the returns from Gravesend came in. A jubilant roar almost lifted the roof of Tammany Hall. McKane had delivered the vote, several thousand for Cleveland, and barely enough for Blaine to compose a football team. Cleveland won New York by a little more than one-thousand votes.

When McKane walked down Surf Avenue after the election, people were in awe at the man who had put Cleveland into the White House. McKane and a large delegation of his stalwarts were invited to Cleveland’s inauguration. They paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue, and then attended the Inaugural Ball. When they got back to Coney Island, they were greeted like conquering heroes by a large crowd.

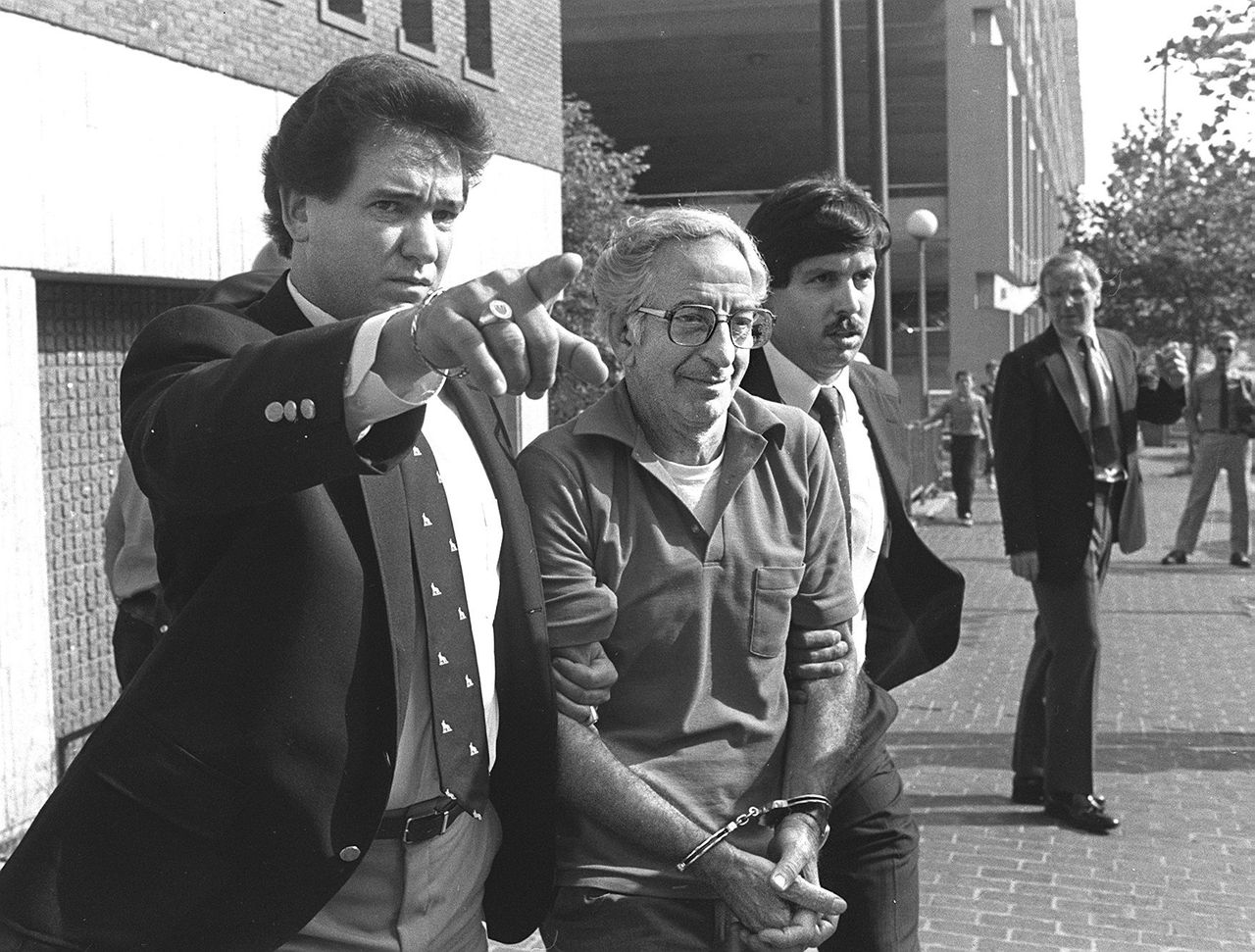

On Election Day, Nov. 7, 1893, Justice Joseph F. Barnard of the Supreme Court in Brooklyn ordered an injunction that restrained McKane from interfering with Republican monitors that were sent to make sure there was an honest election. McKane refused to hand over the voter registry list and actually had the Republican delegation thrown in jail. McKane’s declaration, “Injunctions don’t go here,” would be frequently recalled in the press as the trial unfolded over the next year. McKane was indicted for election fraud with several of his “associates” in December 1893.

Later, when investigators were finally able to get their hands on the voter rolls, there were many suspicious entries. Names such as “Ernest Look,” “Charles Faker” and “Eugene Easy” raised eyebrows, as did the high number of voters as compared to the actual voting population of Gravesend. It was discovered that in the 1888 and 1892 elections, at least 1,000 bogus ballots were stuffed into the box in the second and third wards in Gravesend. Inspectors in the districts were instructed to leave blank spaces in the poll lists, which were filled in with false names, to match the number of bogus ballots. Also, people voted numerous times, some as many as 50 times, using different names.

McKane managed to avoid being caught or convicted throughout the 1880s despite several attempts by the New York state legislature. He was finally convicted in 1893 after refusing to turn clearly phony voting tallies over to the Brooklyn Supreme Court. He was eventually tried and sentenced to 6 years in prison but only served two. He died in 1899.

Sources:

http://www.boweryboyshistory.com/

https://brooklyneagle.com/

https://bklyner.com/